The Cornerstone of Film: Exploring Space in Metropolis and Parasite

- Fiona Craughwell

- Apr 10, 2021

- 7 min read

I need to add an immediate disclaimer: if you have not watched Parasite (2019) yet, stop immediately and go watch it. Then return and enjoy a spoiler-free post!

Towards the end of my studies, many of the classes were focused on both phenomenology and space. I become increasingly interested in both of these topics and elected to write one of my final essays on space and how it is the foundation of film. I used a personal favourite and an all-time classic to illustrate my argument: Fritz Lang’s 1927 sci-fi masterpiece Metropolis.

Metropolis is widely written about and discussed for many reasons. It is a cinematic feat, ahead of its time, beautiful to watch and it has a strong message. For me, its most interesting aspect is its use of space. I believe the argument that space is the foundation of film can be applied to several films. One of the films that this notion could be applied to is one of the most celebrated and talked about film in recent years: Bong Joon-ho’s 2019 Oscar-winning Parasite.

Both use space to tell their story. There are many ‘spaces’ in film: the literal space in which the story takes place as well as the country and culture the film comes from, the subtext; what the film is trying to reflect upon or say. The era and culture of the time often influence the film. Metropolis was made during the Weimer Republic days of Germany and Parasite is set in the modern metropolis of Seoul, South Korea. Both films' interrogation of space brings attention to larger questions about society.

Before I get into both films, there is some housekeeping to be done. I have mentioned that space can mean a few things. It can be the literal space you watch a film in, like a cinema or your sitting room, or it can be the place where the film's story takes place. This may be a real-life location or a constructed set. In modern films, it may be a real location combined with CGI. The camera also frames this space, so the viewer is given a focus. A set may stretch on forever, but we are only allowed to see certain parts of it. A constructed space combined with framing has to ability to create meaning without sound or even dialogue.

There are also multiple ways to experience space. One way is to associate with a character and move through space as they do, experiencing it as they do. Another way is to perceive the space through the camera. Although a camera is mechanical and something people would not typically associate with, it can move and see, and so can we. It is more like us than we think. This is the basis of phenomenology. This interaction between viewer and camera allows a viewer to feel like we have moved through the space.

Weimar Republic-era Germany brings with it a set of cultural ideas as well as anxieties and fears. There was a conflict present, a want for modernity and capitalist success, but also a fear about the cost of such success and its effect on people. The film sets used in Metropolis reflect this divide. There is the space of the common, hard-working man and a space for the rich and privileged, those that have gained from capitalist success. The film's protagonist, Freder, is privileged and free to move within both spaces, but is forced to reconsider these very well-defined and established spaces when he falls in love. This is the catalyst for questioning spaces in the film.

The space for the rich and privileged is a dizzying city, furiously busy, with jagged, gothic skyscrapers that seem to have no end. For much of the film, we look at the city from a height, from the office of its founder, who sits above the entire city. It is a space of dominance and opulence. The rich are so high above the city that when they look down, they hardly recognise it. There is a complete disconnect.

Almost all of the space in the city feels too big. Most rooms have ceilings that seem endless. When we move through corridors or onto streets below, we hardly see other people. Everyone has more than enough space. There is great excess. This awareness of space starts the viewer questioning; why is this space so big? So empty? When this space is compared to the one below it, an even bigger question is asked.

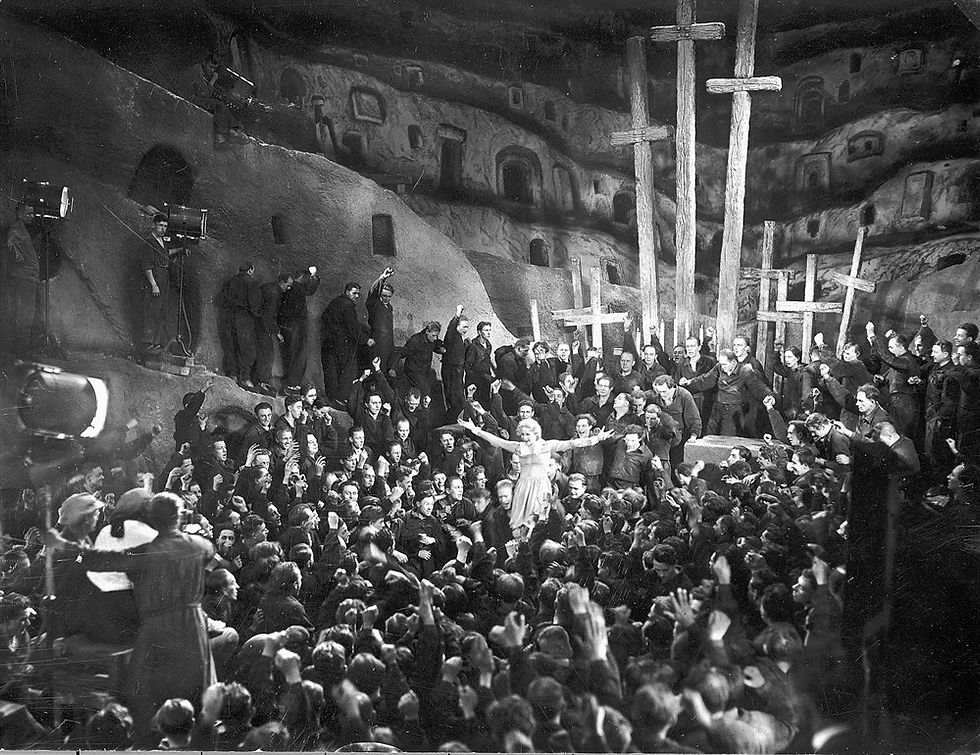

We are first introduced to the second space, in the underground of the city, after a large burst of steam from pipes indicates a shift change. In a cramped and dark tunnel, we see two large groups of workers marching into a tunnel and the other emerging from it. Their heads are down and they move in time like a ticking clock. This world seems to be a measured and unhappy one. It is the home of masses of faceless workers. It is also a chaotic environment and a dangerous one, as Freder discovers on his first venture down there when an exhausted worker can’t take anymore and collapses. This one break in the chain sets off an explosion as Freder gazes at in terror.

The underground world is more organic than the city above. Their homes, or huts rather, are misshapen and not uniform. Every time the viewer moves through this space, they are limited. Ceilings are low and walls are high. The camera does not have space and so neither do we. We feel confined and restricted. Just as with the city above, the viewer must ask: why? Why are the spaces so different? And why are groups separated?

Throughout the film, we have been moving through both spaces. The design of the spaces and the camera movement within these spaces provoke a response from the viewers. Both viewers and Freder have questions after experiencing both spaces. The interrogation of space leads to bigger questions about slavery and human rights. Whether a successful capitalist society is capable of such injustice or, worse, are such injustices necessary for capitalist success?

Metropolis is from 1927, so of course, it is in black and white and also silent. Without the assistance of colour or sound, this film produces two distinctive spaces that say so much about society, success and human beings.

Parasite is an authentic world. There is no set framed by both the camera and the protagonist, Ki-woo. It is a recognisable world with streets and houses, not flying cars and floating highways. While Metropolis has two levels, Parasite uses three to tell its story, making even more use of space to say more than dialogue can. Interestingly, Parasite has a black and white version and being in Korean, its viewer must read the dialogue, much like for a silent film. Considering this, I believe that space is also the foundation of Parasite.

The parasite uses the home space to communicate its narrative. The Kims' home is below street level, essentially a basement under a busy city. Their home is confined by small rooms clearly divided and a low roof that Ki-woo can touch when searching for a wifi signal. What feels most oppressive and claustrophobic is how easily the outside world can enter their home. The street fumigation fills their home, a rainstorm floods it and the nightlight deters drunks from urinating on their home.

On their street, their neighbours' homes are equally confined, leaving only enough room for a car to get through. Apart from that, all the space is occupied. This restriction is only emphasised when Ki-woo walks to his job interview. As soon as he enters the affluent neighbourhood, the street becomes wider and Ki-woo looks small in the frame. While lounging in a luscious garden, Ki-woo notes a huge difference between the two households; he states, “I’m gazing at the sky from home”. Not only is this something he cannot do in his own home, but he is so comfortable in this rich house and lifestyle that he calls it home.

From the moment Ki-woo and his family enter this rich house, with its excessive and seemingly easy lifestyle, they note the unusual personas of the wealthy and find that their own personas begin to change the more wealth they experience. When the actual owners of this home and this lifestyle interrupt the Kims' fantasy, they are forced back to their ‘normal lives'. They return to the cramped spaces filled with other struggling people, but their mind frame has already started to shift.

This change does bring about many internal conflicts. There is a guilt that their whole family has secured employment when they know many struggle. They are also confused that these rich people are nicer than they expected them to be, but it is suggested that they are only ‘nice because they are rich'.

When the third and final bunker space is revealed, it creates another layer. Until now, the spaces clearly marked the divide between rich and poor and showed the unfair division of wealth. I believe this bunker space acts as a leveller and is both a rich and poor space. On the one hand, only the rich can afford to have bunkers in their homes, but they are cramped and restricted like many poor homes. When the bunker is discovered, the Kims', who lived a rich fantasy, knows this will bring about issues that may jeopardise their carefully balanced plans.

The space ultimately reminds them of who they are, where they belong, and that they cannot escape their poverty. Ironically, Mr Kim can not understand how somebody could live in a bunker, but he is reminded that many people live in basements. After all, don’t they? Or had they for a brief moment forgotten? The bunker space shows how your mind frame can change depending on what side of the financial line you stand on. At the film's end, both Ki-woo and the viewer realise the only way out of their predicament is to become rich, a sad reality that they and many others cannot escape from.

Parasite uses space to tell its story. While this is helped by cleverly-used dialogue, each space is telling us something. It is causing us to question the problems in our society that we all know exist. Sometimes no matter what you do - work hard, go to college -, it seems the odds are always going to be stacked against you.

For me, space is the foundation of both of these films and cinema as a whole. Without colour or sound, each space is telling us something. There is an event that is the catalyst for integrating the different spaces. Metropolis challenges the fears and moral ambiguities of Weimer Republic German. Parasite challenges a more modern issue of the wealth divide, the limitations and notions in our society that prevent you from even having a chance. In a way, both films are saying the same things; they are just coming from different eras, but moreover, and very cleverly, Parasite introduces a third space, a more moral space and questions if we change when we get a taste for the high life as well if we can ever escape poverty or will it always pull us back down?

Comments