Reexamining the foundations of cinema and its emotional impact: In The Mood For Love and Prisoners

- Fiona Craughwell

- Jul 10, 2021

- 6 min read

This is not the first time I have spoken about ‘space’ when it comes to cinema and I really believe that it is the foundation of cinema. I already have a post expressing some of my views on the matter. Space is a combination of a few things. It may be a set carefully designed, a real-life location or a computer-generated location. This space is then framed by a camera, what space the camera wants us to see (or maybe what it will allow us to see), creating a space within a space. As we can see, space is a very planned and well-thought-out element in the filmmaking process.

There is, of course, another force at play here that adds to my point and that is phenomenology. This can be a method by which we experience space. Of course, we may move through space as the protagonist does if we find ourselves associating with them, but we may also experience the space through the camera. We associate with the camera; it has eyes and ears and it moves in the space. It is like us looking at the action, not part of it. It is a physical representation of a viewer.

However you perceive and experience a space, it conveys a message. It is used as part of the story to tell us something, to make us feel something and - most impressively - it does not have to tell us anything. An emotion or a feeling is evoked just by using the space we are in. It shows us. It doesn’t tell us what to feel or think or experience. We are allowed to experience it in our own way and come to our own conclusion. This is why I believe space to be the cornerstone of filmmaking.

When I spoke about space before, I was proving my case. I used examples from two films infamous for their use of space: Parasite and Metropolis. But these two films also had cultural and political points to make, which they do through very effective use of space. This time I am looking at space from a different perspective. Looking at both In The Mood For Love (ITMFL) and Prisoners, I am questioning how two films that use space in such a similar manner evoke such different emotional responses. Both films have no crucial message, no agenda to push. They are simply stories, but, much like Parasite and Metropolis, space is a crucial element in both ITMFL and Prisoners, both for the story and the emotions the story is trying to evoke.

Both ITMFL and Prisoners could have easily made it into ‘Fi’s Favourites’ (and who knows; maybe they still will). Wong Kar-Wai’s In The Mood For Love (2009) is hands down one of my favourite films of all time; it even makes it into the top three. I love it so much so that I attempted to work it into almost every college assignment I had, but managed to restrain myself to just one mid-term essay.

The word masterpiece gets thrown around a lot, but if there was ever a film fitting and worthy of the title, it is ITMFL. This film is perfection. It is, of course, not just its use of space that makes it a work of art (although it is crucial), but it is the sum of all of its elements combined, working so perfectly together, that make this film such a joy to watch and experience. It seems so effortless, but much like a busy hive, much work and planning are placed into each element, all combining to make one perfect thing.

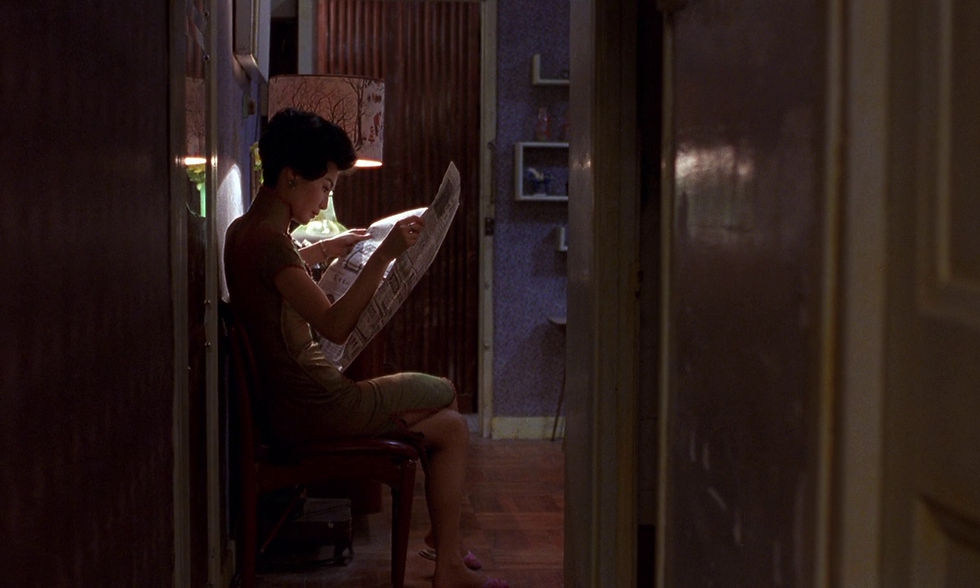

Enough gushing, though. ITMFL follows neighbours Chow Mo-Wan and Su Li-Zhen. That's all I’m giving you plot-wise as you should really go into this film knowing as little as possible (yes, I see the irony). Much of ITMFL is centred around the mundane: work, home, cooking, etc.; the everyday chores of life. Wong Kar-Wai wants us to focus on such small, seemingly insignificant tasks of the everyday as within these tasks there are spaces and within the spaces the story takes place, but, moreover, in these spaces emotion is brewing.

The apartments are pokey, cramped and with hardly enough room for two people to live comfortably. When Su Li-Zhen goes to the kitchen, when she opens her door to leave for work, when she returns with her groceries; Chow Mo-Wan is there. He is not stalking her. He has no choice but to be there. There is no room for him to be anywhere else.

One of the film's most iconic scenes and one of my personal favourites captures the film's brilliant use of space to convey emotion. Su Li-Zhen frequents a local noodle vendor for her meals, as does Chow Mo-Wan. They walk through narrow street corners, unaware that the other is about to appear from around the corner and, with no time to react, they pass each other with a polite but startled smile with the narrow streets and spaces giving them no choice but to graze past each other. We feel the hairs on their skin stand up as they are forced into an intimate space. The first corner skews their view, not allowing them to prepare for the encounter. The second corner provides relief and space to recover from the close encounter.

Wong Kar-Wai is showing us what to focus on by removing all other possible distractions. The tension it creates, the atmosphere it evokes, these encounters, begin to occur because of the lack of space the characters have. Space is nearly dictating the story. At times it feels as though Kar-Wai is the puppet master forcing these two together.

Sometimes scenes are played out in slow motion or often the film will even go back, showing you another perspective that was obstructed from the viewer by the space. Both techniques change the space, so even the same space can feel different when we are stuck there longer than we normally would be and when another angle is revealed.

ITMFL’s space is used to portray a deep intimacy. His characters live in cramped conditions, nearly on top of one another. They are practically forced into these spaces. From this, great emotion is formed and remains long after the film has ended.

Oddly enough, I believe Denis Villeneuve’s 2013 Prisoners is more similar than not to ITMFL. When Keller Dover and Franklin Birch's daughters go missing, Dover takes an aggressive approach and takes matters into his own hands. This aggression and violent approach lead to many tight spaces and many characters are forced into spaces such as these, but a totally different emotion is created.

As with ITMFL, there are many factors at play that create the film's overall atmosphere: colour, pacing, lighting etc. Perhaps it is elements such as these that create an overall much more threatening and dark atmosphere, but space is also a factor.

Unlike ITMFL, this is not a story from everyday life. This is not the mundane. This is a traumatic situation full of heightened emotions, but, like ITMFL, this situation is filled with many restricting, confined spaces; cars or basements filled to the brim. Moreover, it's not that all the spaces are restricting, but they are made to feel that way. Trees in vast woods end up obscuring your view and the longer you stay there, the more the trees begin to look like something else and you start to look over your shoulder. Rundown houses filled with empty rooms are restricted to one corner. Many of the spaces are unusual, such as a basement with no stairs. Many are dark and need to be explored and revealed gradually, which the characters do for us.

In ITMFL, we gradually get to know the characters and I believe anyone would see them as ‘good’ or human, at least, flawed as we all are. Here characters that are ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are forced together into these spaces. So, that intense, intimate emotion we feel in ITMFL is altered, although the situation in Prisoners is still intense. Still, the intimate is replaced by the intimidating and threatening and the skin-to-skin closeness of ITMFL feels like an invasion of personal space in Prisoners.

Su Li-Zhen and Chow Mo-Wan are initially forced into these spaces, but, after a while, they seek them out longer for closer interactions that can only be found in such locations. In Prisoners, it is only forced. I set out to ask if these films were more similar or more different. As I mentioned, a film is the sum of all of its parts and that’s why they feel so different, but in terms of the use of space, ITMFL’s mastery is almost replicated in Prisoners to a totally different effect.

Comments